In the context of electricity, demand side management is the deliberate modification of consumer demand for power through various methods such as fiscal incentives or education.1 These efforts are traditionally undertaken by governments, utilities, and interested non-governmental organizations.

Today, demand side management generally means an effort to reduce overall demand, or to move demand to different times. In the past however, demand management was often undertaken to encourage increased consumption.

In this piece, we examine why the focus of demand management has changed in the last several decades. We will also look at some specific tools that are currently being used to reduce demand or shift it to different times. In closing, we will discuss why this topic is of such importance with regards to renewable energy.

Contents

Why now, but not 50 years ago?

Demand side management is being avidly pursued today for many reasons. These reasons range from economics to pollution to climatology. We will begin first with a look at the reasons why policies intended to do exactly the opposite thing were advocated in the past.

The history of electrical power production has been marked by reductions in real price (inflation adjusted) as the technology and economies of scale improved. So as time passed, a given amount of electricity cost progressively less to produce.

As new power generation was added, more consumption was encouraged for at least two major reasons:

- Investors who had created power plants wanted to see their commodity (electricity) valued highly, so they encouraged greater power usage.

- Energy usage is usually strongly correlated with economic growth. In planned (or mixed) economies there were often significant subsidies on energy resources because of the powerful stimulating effect that low energy prices can have on an economy.2

To put it in another way, in the past there were clear reasons for governments and many corporations to encourage greater power usage. We live in a different world today. The future of electricity is looking to be quite different from the past in this regard.

While real costs of electricity production historically fell for many decades, they are expected to rise in the coming decades. Also, the normally strong connection between increasing energy usage and increasing wealth is becoming very disputable, especially in the richest nations in the world.

Energy usage and wealth diverging?

As a simple illustration of why this may be so, see this Gapminder graph of Energy Usage per person in tons of oil equivalent (toe) vs wealth per capita. The trend of the points near the left (poor) side of the graph rise steeply, indicating that increasing energy usage and increasing wealth are correlated. However, at around 4 boe per person you can see that the trend seems to flatten out substantially and becomes much more random. This is an indication that increasing energy usage stimulates developing economies more than developed ones.

Let us be clear that this is not proof that increasing energy consumption in rich nations is unrelated to economic growth. Recent studies have demonstrated that increasing energy consumption in OECD nations does cause some economic growth. It certainly appears though that there are diminishing returns as humans use more and more energy. Wealth and well-being are becoming increasingly de-coupled from energy usage as nations become more advanced.

This makes sense when looking at the aggregate perspective: The poorest countries of the world cannot easily afford heating, roads, and industrialized food production. The developing nations of the world are still building the infrastructure to meet their basic needs. Conversely, the industrialization of the richest countries in the world has slowed or even reversed.

The rich world has met its primary infrastructure needs for now, and can be regarded as being in what we might call ‘maintenance mode’. This is not to say that we are merely maintaining existing infrastructure. We are also not claiming that the industry in rich nations is stagnant in any way. We are merely saying that in order to continue to meet and even exceed our basic needs in rich nations we do not need to industrialize our society more than we already have.

Policy changing to reflect the new facts

What does all of this mean from a policy perspective? It no longer makes sense for governments of the developed world to encourage their people to consume more power. When it is clear that using our energy more efficiently contributes more to our economic well-being than producing more energy, policy recommendations are clear.

Around the world there has been a movement towards policies that encourage energy efficiency. Here are some general categories that these policies fall into:

- Subsidies, rebates, or tax-deductions for appliances, homes, and vehicles that meet energy-efficiency standards.

- Power rates that escalate with increasing consumption. That is, someone who uses twice as much power as you do per month will pay a bit of a premium per kilowatt hour.

- Time of day pricing of electricity or a ‘smart grid’. Since peak electricity costs so much more to produce, charge people more for their consumption during peak times. The implementation of time-of-day pricing tends to encourage the shifting of power usage away from peak times as well as a general reduction in demand.

- Dispatchable demand management, or dispatchable loads, are programs through which people or companies can allow some of their appliances or machinery to be shut off by a signal from the grid operator. If you don’t know what the term ‘dispatchable’ means in the context of power generation, you may be interested in reading another issue of the Renewable Energy Review which deals with dispatchable power from renewable sources. We go into more detail about dispatchable demand management later in this article.

The cost-effectiveness of energy efficiency

It has been found that one dollar used to increase the energy-efficiency of our society can save about two dollars that would have needed to be spent on new power production equipment or fuel.3 This is particularly noticeable for demand management techniques that reduce the peak power usage, since peak power tends to be vastly more expensive than baseload.

How big of an overall effect can these policies have on our power grids? The EPA in the United States estimates that over 50% of projected load growth before the year 2025 can be avoided with energy efficiency policies.4

Time-shifting vs demand reduction

Important to note that peak demand management generally does not reduce the amount of energy used, it merely moves it to another time. We can think of this as shifting the consumption away from the expensive sources used at peak times toward the lower-cost sources that provide power at off-peak times.

Demand side management in general however can reduce the energy used. For instance if the government or utility created small rebates for CFL light bulbs and energy efficient home construction or retrofits, these efforts would lead to a reduction in the total energy demanded.

Time of day pricing: Low hanging fruit

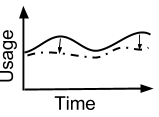

Exposing consumers to some degree of price fluctuation to reflect generation costs has the effect of flattening the demand curve. The introduction of time-of-day pricing tends to reduce the demand for electricity during peak times, and distribute some of the displaced demand to other times of day.

Exposing consumers to some degree of price fluctuation to reflect generation costs has the effect of flattening the demand curve. The introduction of time-of-day pricing tends to reduce the demand for electricity during peak times, and distribute some of the displaced demand to other times of day.

Normally power users are relatively inflexible with their power use. However, today we are empowered by technologies that can manage consumption based on energy market prices. It is even possible to inexpensively hook up almost every appliance in a home to a central system that can turn them off at high-cost times.

Energy intensive industries

For example, many energy-intensive industries try to consume all of their power during low demand periods when electricity is produced at a very low cost. Energy intensive industries were early adopters of this practice for several reasons.

- They can have a major effect on the grid, so power utilities would often create contracts with them regarding cooperation for a more stable and cost-effective power grid. Big energy users generally have to negotiate unique contracts with their electricity providers. Often these contracts include fiscal encouragement for off-peak power usage and dispatchable load. If you don’t know what dispatchable load is, we go into it in more detail later in this document.

- Energy intensive industries tend to be very conscious of where their electricity is going, and when it is being demanded. This is due primarily to the fact that their energy costs can be tremendous. If there is net fiscal gain to be made by consuming off-peak, they will very likely implement such a policy.

- These industries have had the technological capability for a long time to automatically monitor and adjust their consumption. These technologies however are only now seeing widespread adoption to the public for use in homes and small businesses.

Dispatchable demand management

What does dispatchable demand mean? In a very simple sense, it means that grid operators have the ability to turn off some electric devices that are consuming power. In this way the grid operator can reduce demand at certain times when it would be overly expensive or dangerous to try to meet the demand merely through increased supply.

The owner of the electric device usually has some say in the matter. Dispatchable demand management programs are usually voluntary. The grid operator offers some financial incentives for people and companies to sign up for the program. Generally the payment is some fraction of the money ‘saved’ by not having to turn on expensive peak-matching power generation at peak demand times. The more peak power you can save, the more money you can get back from your power utility.

In Ontario there is a program called Dispatchable Loads that does exactly this.

Heavy usage industries

Another fact of life in the power industry is that the grid operators do reserve the right to cut off access to power on short or no notice in order to preserve the integrity of the grid. This means that major power users, such as industries, will work out contracts with the grid management system about whether they can be shut down, and on how short of notice. Through this system a heavy power user can negotiate for lower power rates or other preferential treatment because they are being a good ‘energy citizen’.

What this means is that the heaviest power users may not have much choice in the matter. In order to acquire power they may need to sign binding contracts with the grid management company.

Why implement this policy?

Offering this choice to all companies and individuals can create a very powerful grid management tool.

- Being able to turn off several hundred megawatts of demand is generally vastly preferable to having to fire up a gas turbine on short notice in terms of both cost and emissions.

- Dispatchable demand is fast, perhaps even on the order of seconds. This makes it incredibly useful in the same ways that energy storage is useful. For a deep look at why we need fast-responding power systems, see the previous issue of the Renewable Energy Review on the topic of why electrical energy storage is useful.

- Technology exists today and is quite affordable. This was not true in previous decades, but is definitely true today. Smart meters are not very different from standard meters in cost. Other useful electronics, such as the computerized systems that can manage power usage for an entire home, have also become quite affordable. While it may be true that these costs are likely to continue to go down slowly over time, this does not change the fact that there is great opportunity today for tremendous efficiency gains if we invest in this technology today.

- Citizen and business participation in a power market. In a sense this is allowing the individual to partake in some aspect of the power grid. People often convince themselves that nothing they personally do matters to society at large. This is clearly not the case when many people contribute to a central planning authority. For example, in the city of Toronto, the grid management company Toronto Hydro can use dispatchable demand management to reduce the load by 50 megawatts in a short time.5

Demand management plus renewable energy

You may have been asking yourself, why are we talking about demand management in a publication named the Renewable Energy Review. The connection may not be clear, so we will spend a bit of time looking at why we believe demand management is incredibly important for a deep discussion of the possibilities for renewable energy in our world.

Playing catch-up

With the implementation of demand management policies, the growth of demand will be slowed. Renewable energy technologies are in a stage of rapid innovation as several of them have recently become economically viable as grid power sources. It is difficult enough to build a renewable power grid without the demand growing rapidly. The slowed growth of demand will help us replace a larger percentage of our conventional generation in a given amount of time than we otherwise could have.

Reduced demand is better than green power

Every unit of energy we harness and consume causes some amount of environmental damage. Reducing our total usage reduces our total impact. This applies even to the renewable power systems of today. There is no power system that we yet have that has zero environmental effects. Our understanding of physics, engineering, and ecology leads us to claim that such a technology, if possible, is spectacularly far in the future.

In case that last point is misunderstood, we would like to restate it: We should definitely be investing in renewable power infrastructure and innovation. Our point is that we should also be investing in demand management because of its myriad of benefits to our society. Demand management won’t make the difficulty of ‘greening our grid’ go away, but it can help to reduce the difficulty of reinventing the way we power our society.

Renewables are not very dispatchable

Dispatchable means power that you can turn on when you need it. Only a few implementations of renewable power can deliver power of this sort. We have looked in detail at some of these sources in previous issues. If you are interested in which renewable energy sources can do this, read about hydro, solar thermal, and biomass.

The creation of dispatchable loads is an excellent way to improve our grid management ability without necessarily adding more dispatchable power generation to the grid. This would allow us to more extensively utilize variable output technologies such as wind, solar, tidal, and run-of-river hydro.

These forms of renewable energy can be very cost-effective for the delivery of energy, but cannot always be counted on to be producing power when you need it. The combination of these cost-effective energy technologies with dispatchable loads is a powerful concept indeed. We will still need dispatchable power on the grid, at least for the foreseeable future, but the implementation of dispatchable loads will allow us to use greater quantities of variable or intermittent power sources.

Call for submissions

This concludes the eighth installment of the Renewable Energy Review Blog Carnival. For a complete list of all publications in this series, see our post regarding the launch of the carnival. If you are interested in submitting an blog post or article to this publication, see our submission page on the Blog Carnival website. This carnival is currently published weekly or bi-weekly, and we are always interested in seeing new material.

The intent of this publication is an ongoing investigation of the progress and potential of renewable energy in our world. Our goal is to collect the best writing and news on the subject of renewable energy projects and policies. We have observed that humanity is innovating rapidly as the energy security of the future becomes a global priority.

- Wikipedia: Energy Demand Management. Accessed December 7th, 2010. [↩]

- Wikipedia: Energy demand management. Accessed December 6th, 2010. [↩]

- Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency: The Solutions to Climate Change. Beyond Nuclear.org. Accessed December 7th, 2010. [↩]

- Understanding Cost-Effectiveness of Energy Eficiency Programs. United States Environmental Protection Agency. December 7th, 2010. [↩]

- Volatile energy prices demand new form of management. Business Green. Accessed December 8th, 2010. [↩]

2 thoughts to “Demand side management to help build a renewable power grid”